by Steven D. Johnson

by Steven D. Johnson

Racine, Wisconsin

(Page 2 of 3)

Previous Page

1

2

3

Next Page

Rag-In-A-Bag...The Controversy Continues

A passing comment in an article a couple of months ago stirred up the proverbial hornet's nest, resulting in my clarification and apology last month and now a formal (and tentative and caveat-laden) retraction of my apology.

While extolling the uses for many common household items in our woodworking shops, I mentioned that zipper equipped plastic food storage bags could be used to dispose of smelly finished-soaked rags and brushes. Some, well, many readers chastised me for a practice that might lead to spontaneous combustion.

Those of us who are engaged in long-term wedded bliss know that quick and sincere apologies are a proven coping technique we must master. Conditioned as I am, I may have recanted too quickly.

When someone with the title "Distinguished Professor Emeritus" suggests my apology may have been premature or mistaken, I listen. According to reader Donald H. Lindsley, "The fire danger...comes from an oxidation reaction. As long as you are isolating the rags from air (~21% oxygen) you are also preventing the oxidation from occurring – after any oxygen trapped in the bag has been used up." Professor Lindsley suggested that an experiment might be in order, and I agree. Even grown up boys sometimes like to play with fire.

When I first started putting my oily and finish-soaked rags in plastic storage bags for disposal, it was after seeing the hazardous material procedures followed by one of the big-box home centers. Throughout the day rags soaked in paint and thinner are tossed into a flammable materials bucket with a spring-loaded tight fitting lid and lined with a plastic bag. Each night the plastic bag is removed, closed tightly, and placed in a larger flammable materials holding container with a secure lid. I reasoned that keeping the air out was the secret to avoiding catastrophe, and likewise reasoned that a zipper food bag could accomplish the same thing, albeit on a smaller scale, in my shop.

Still, to be sure, I let the rags dry outside for a bit, then place them in the bag, seal it, and dispose of that outside, away from other flammable materials. The question is, could an oily rag really oxidize and create heat inside a closed plastic bag?

|

Figure 7: Spontaneous combustion,

anyone?

|

So, following the good professor's suggestion, I designed an experiment. Cotton rags were cut into exact same size four square foot squares. Each "experimental batch" consisted of three rags. I set up a 2 X 6 on concrete blocks, well away from my shop, and attached paper bowls 16 inches apart, each secured to the board with a thumbtack. In the first bowl, labeled "A" I placed three rags. One rag was soaked in tung oil and the other two were soaked in mineral spirits. Bowl "A" was to be my "control."

The remaining bowls all got three rags similarly soaked (I weighed the bowls to make sure each batch of rags got the same amount of finish and thinner), but the rags were placed in zipper-style plastic bags. In batch "B" part of the air was squeezed out. In batch "C" air was blown into the bag before it was closed (think balloon). Batch "D" was to simulate a food storage bag whose zipper leaks, so several pinholes were punched in the bag. Batch "E" was the other control. All the air was carefully squeezed from the bag and it was sealed tight, per my original process and recommendations.

|

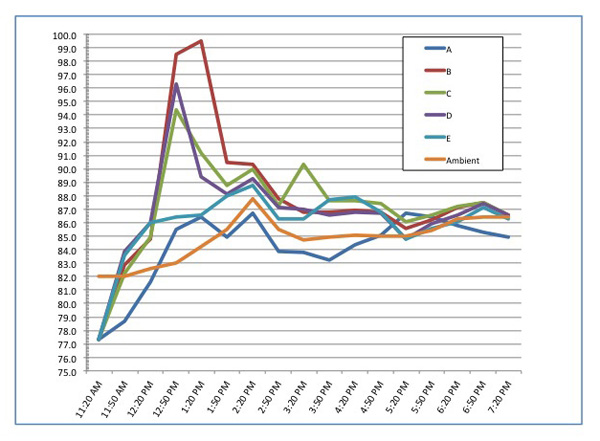

The experiment commenced at 10:20 AM and temperature readings were taken every thirty minutes using a non-contact digital thermometer. Ambient air temperature was also recorded. I concluded the experiment eight hours later, and following is a chart of the temperature readings:

|

As you can see, at the two hour mark, the internal temperature in sample "B" had reached 99.5°F, sample "D" reached 96.3°F, and "C" topped out at 94.4°F. The temperature within sample "E" measured 86.6°F, just barely above the ambient temperature outside. By the third hour, the minor temperature spikes had fallen, and throughout the afternoon, the temperatures fluctuated within a narrow band very close to the ambient air temperature.

So what did the experiment show? Bags "B," "C," and "D" all had access to some air and an oxidation reaction did begin. Sample "E," with all the air squeezed out, rose to slightly above ambient air temperature and never any further. Sample "A," the control sample with no plastic bag, actually registered cooler than the ambient temperature in most samplings until late in the day.

True scientists will note some potential flaws or areas where variables could creep into my experiment. Wind currents, the dappled sunlight, and not maintaining a temperature probe in the middle of the mass of rags are some shortcomings and sources of possible inconsistencies in the data. But there were some legitimate findings. The rags in bags with air, or access to air, began an oxidation reaction but never achieved anywhere close to the 400+°F needed to combust. Once the oxygen was consumed, the reaction stopped. In the pin-holed bag "D" the oxidation reaction also stopped, I suspect due to the evaporation of the volatile components of the mineral spirits. In fact, I suspect it was the evaporation of mineral spirits that actually served to cool the control sample "A."

There are a couple of conclusions that can be made:

- If you are sure that the plastic bag you are using can be sealed airtight, and if you squeeze out all the air, my originally described disposal method should be fine. Still, in an abundance of caution I will continue to allow my finish-laden rags to air-dry and then put them in air tight zipper-closure plastic bags and dispose of them outside my shop. How was that for a caveat-laden retraction to an apology?

- An inference can be made that in order for spontaneous combustion to occur, there must be enough mass (a big enough wad of rags) to provide insulation and heat buildup and there must be enough oxygen to fuel the oxidation reaction. My control batch of three rags was just not enough to insulate the core and allow the heat to build up. The VOCs simply evaporated too quickly. Therefore, relatively small quantities of finish-laden rags are less likely to cause a problem, but follow safe disposal methodology anyway.

Be advised...air quality regulations are broadening and restrictions may someday be so onerous that we will be forced to find ways to dispose of rags laden with volatile organic compounds (VOC) so as to not allow their evaporation into the air. It might be a good time to come up with alternatives to air-drying and produce a common, standard recommended methodology for woodworkers. Perhaps creative suppliers will provide a market-based answer.

(Page 2 of 3)

Previous Page

1

2

3

Next Page

Return to Wood News front page